What Los Angeles Dodgers can expect from Roki Sasaki in 2025

The Monster of the Reiwa era has arrived.

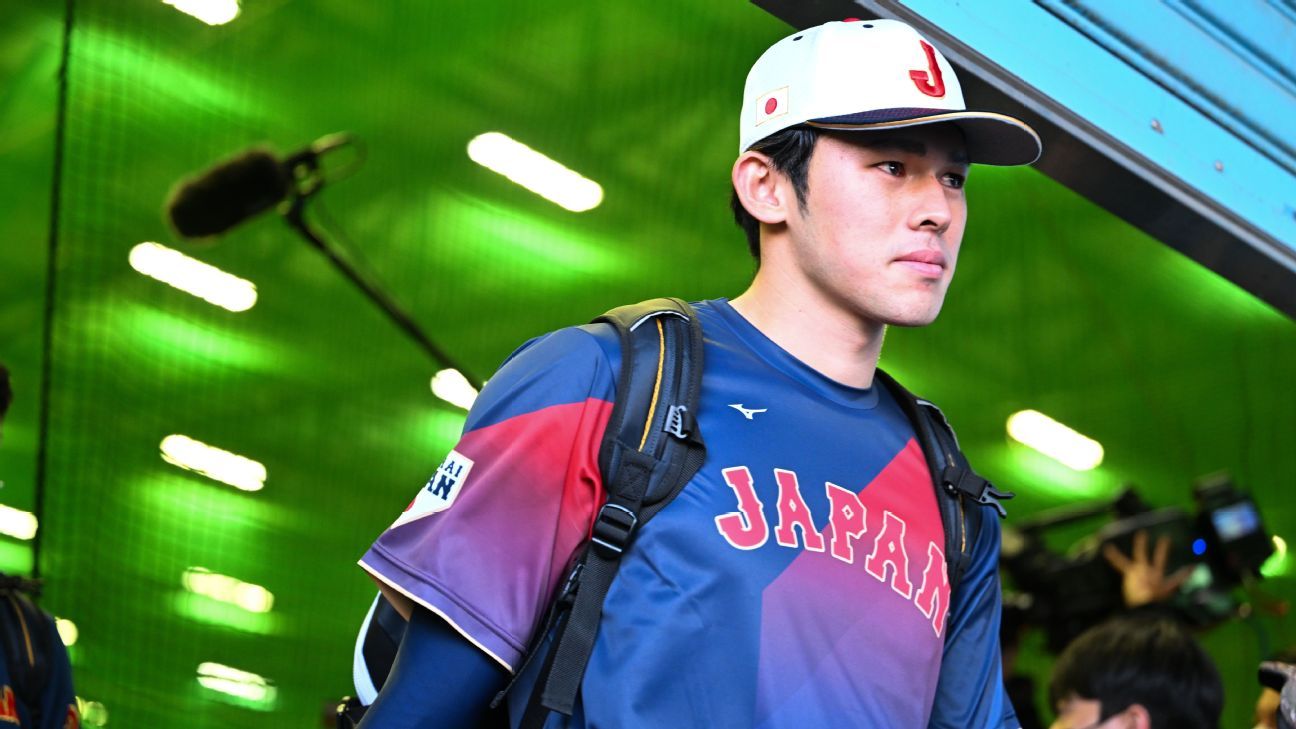

On Friday night, Japanese right-hander Roki Sasaki chose the Los Angeles Dodgersas his major league team and will soon grace American baseball fans with his devastating arsenal and captivating upside.

Sasaki is only 23 and has had domestic evaluators salivating about his potential since he was a teenager. Armed with a triple-digit fastball, a mind-bending splitter and the determination of a budding ace, Sasaki’s posting last month shook up the industry and had virtually every team dreaming of adding him to its rotation.

In four years with Japan’s Chiba Lotte Marines, Sasaki posted a 2.02 ERA, 0.88 WHIP, 524 strikeouts and 91 walks in 414⅔ innings. In one two-game stretch in April 2022, he twirled a perfect game — highlighted by 13 consecutive strikeouts, an NPB record — and followed it with eight perfect innings. Now, he’ll attempt to follow Yu Darvish, Yoshinobu Yamamoto, Kodai Senga and Shota Imanaga, Japanese aces who all made the transition to Major League Baseball rather smoothly.

One day, Sasaki could be better than all of them.

But he’s not there yet.

ESPN spoke to numerous scouts and evaluators who have spent years tracking Sasaki in Japan’s Nippon Professional Baseball league, and the picture they painted was one of a gifted, determined pitcher with promise, but one who, despite the hype that has surrounded him since high school, is not yet fully formed.

So what can the Dodgers expect from him in 2025? What follows are the five biggest takeaways from the scouts and evaluators on Sasaki, for this coming season and beyond.

1. He won’t be an ace — yet

Leading up to his first round of meetings last month, Sasaki provided his suitors — believed to be at least eight teams — with what he called a homework assignment. All of them had the same task: To diagnose why his fastball velocity dropped last season in Japan, and to outline their plan to ensure it never happens again. To those who have tracked him, it said a lot about the 23-year-old phenom — that he’s confident, but also self-aware. That he’s a long-term thinker. And that though he recognizes he can get better, he’s hell-bent on being great.

“There aren’t a whole lot of 23-year-olds who are going to be assertive enough to ask eight major league front offices a question like that,” said a high-ranking executive who has seen Sasaki since high school. “Most kids that age are either in awe of that situation or hanging on for dear life.”

Many who followed Sasaki believed his choice of a major league team would come down to a single factor. Location would matter, as would market size. The presence of Japanese teammates wouldn’t hurt, nor would the possibility of sustained winning. But the winning suitor, they thought, would be the one that best presented its case to make him better.

“What he wants is to be a really good starting pitcher,” one scout said, “and he knows he’s not there yet.”

Sasaki could have waited two years and likely attained a nine-figure deal as a traditional free agent. Instead, he made himself available as an international amateur and signed the equivalent of a minor league contract because he wanted to expose himself to the world’s best hitters as quickly as possible. And for as admirable as that approach might be, it also serves as a reminder that despite Sasaki’s outsized talent, he is not a finished product.

How much work he needs is debatable. One scout who watched Sasaki extensively in NPB wouldn’t be surprised if he started the 2025 season in the minor leagues. Another evaluator pushed back on that, noting the quality of his stuff is already good enough to get major league hitters out consistently. But, he added: “Anybody who thinks they’re acquiring a top-of-the-rotation starter at the beginning of the year is not being 100% honest with themselves.”

The instant success of Japanese pitchers such as Imanaga, Senga and Yamamoto in recent years has helped to heighten the expectations for Sasaki. But it overlooks the fact that Imanaga, Senga and Yamamoto arrived in the United States when they were in their mid-to-late 20s, having accumulated more professional experience and far more innings. They were fully formed, or at least close to it. Sasaki is not.

“This guy has the ability to be better than them by a really wide margin,” the exec said. “But he’s not there yet.”

2. Even on Day 1, ‘nobody has a shot’ against his splitter

“Vicious.”

“Devastating.”

“Double-plus.”

“Equalizer.”

“F—ing nasty.”

Those were terms used by scouts to describe Sasaki’s splitter, which has frequently warranted the rare 80 grade from evaluators. Out of his hand, it holds the appearance of his fastball, which has reached 102 mph. But then it travels in the 88-to-92 mph range, with minimal spin, and then it plummets, dropping either straight down like a traditional splitter or slightly glove side like a cutter.

When one scout first saw it three years ago, he swore it was a slider. Then he looked at the Trackman data and saw it possessed virtually no spin. Then he saw another, noticed downward action and realized he had witnessed what might be the world’s best splitter. The quality of that pitch lessened slightly during the 2024 season, some evaluators say, but it is no worse than a 70-grade pitch.

In the words of one front office executive who has spent a lot of time watching Sasaki in Japan, “It might be the best secondary pitch in the world.”

“Japanese hitters are confused, and they can hit splitters way better than major league hitters,” one scout said. “Nobody has a shot against this pitch.”

3. His fastball is electric, but it needs work

The big question surrounding Sasaki — from Sasaki himself — revolved around the velocity dip he experienced in 2024, while still managing a 2.35 ERA and striking out 29% of hitters. His four-seam fastball went from averaging 98 to 99 mph to more like 96 to 97. Some pointed to a brief bout of shoulder fatigue while others chalked it up to experimenting with other pitches. Most, however, dismissed it as a major concern and brought up a slightly bigger one:

The quality of the pitch.

What can make Sasaki devastating is that he pairs a mind-bending splitter with a fastball that, even last year, can reach triple digits. But that fastball has been described by some as flat. He can get away with it in Japan, in a part of the world where hitters aren’t as accustomed to seeing high velocities, but not here.

“Major league hitters, they’ll time you up,” a longtime scout said. “You can throw 200, and they’ll figure you out.”

Sasaki spent a lot of his 2024 season adjusting to that, throwing slightly fewer splitters and four-seamers, incorporating more sliders and cutters — two pitches that, for him, can be one and the same, according to some scouts — and introducing a two-seamer. Evaluators see Sasaki as someone who is motivated to improve his four-seam fastball that, at times, plays down but also wants to figure out ways to offset it.

The key, many believe, will be establishing better command of the four-seam, particularly inside to right-handed hitters, but also incorporating other pitches that will make him less reliant on it and allow the splitter to act as a true putaway pitch. One scout who has followed Sasaki for years presumed that big league teams suggested he maximize his two-seamer and slider/cutter usage as a means to sustain him once major league hitters become more familiar.

The thought is that Sasaki has the aptitude for it, having already shown that he can vary the depth of a slider that has flashed plus movement. But the floor here is still quite alluring. As one scout said: “A hundred is still a hundred.”

4. His workload will be a concern, at least initially

Sasaki starred in Japan’s prestigious high school baseball tournament, Summer Koshien, where teenagers are exposed to workloads that are unheard of on this side of the globe. In one eight-day span, he threw 435 pitches, a number major league starters won’t often reach in a month. But Lotte treated him conservatively upon drafting him No. 1 overall in 2019.

Sasaki was limited to only bullpen sessions and simulated games in his first pro season in 2020. From 2021 to 2024, his innings totals were 83⅓, 129⅓, 91 and 111.

In short, Sasaki will have to be eased into a major league rotation. Starting virtually once a week as part of a six-man staff will certainly help, but it won’t be enough to avoid what would be a considerable innings jump.

“That’s been one constant throughout his career — as good as he’s been, as much as he’s looked like one of the best pitchers in the world, he has not handled a workload we’re accustomed to seeing from major league starters,” a scout said.

Durability concerns follow Sasaki not just because of his track record, but because he throws exceedingly hard for his thin build. Lotte lists him at 202 pounds, which isn’t much for someone who is almost 6-foot-4 — and his weight is seen by some as generous.

“He’s super athletic, naturally strong,” another scout said, “but you don’t look at him and think ‘workhorse.'”

Some believe that will come. A front office executive believes Sasaki can eventually get into the 225-pound range, the added weight serving as a “shock absorber” for the explosiveness of his delivery. A major league pitching coach who has reviewed lots of Sasaki’s footage called him an “efficient mover” and “tight rotator” with “great brakes at release,” allowing him to keep his body stable despite applying a lot of force with his delivery.

“They throw so much over there,” the pitching coach added, “I don’t have a huge worry about him holding up.”

5. There will be growing pains — but he can handle it

Sasaki has been described as a deep thinker with a burning desire to master his craft, but also someone who is guarded and doesn’t trust easily; a product, some have speculated, of what he has had to overcome — the trauma of losing his father to the tsunami of 2011, the outsized expectations he has carried since high school, the public backlash he endured because of leaving Japan early.

In the United States, Sasaki will face the same transitional challenges of every Japanese player, from a new ball to a different mound to a separate culture. But given his age, the biggest adjustment, one front office executive believes, will be “fitting in with teammates.”

“In Japan, it’s a smaller country,” the exec said. “The travel isn’t as extensive. You don’t find yourself in as many different places. St. Louis is way different than L.A.; New York is way different than Atlanta. Spending that amount of time with guys that he does not know and don’t know him and aren’t entirely aware of what he’s accomplished to this point in his career, and having a cultural gap between him and his teammates — I think that will be above and beyond the most challenging thing.”

His ambition, at least, could carry him. Multiple evaluators were impressed with the way Sasaki navigated the 2024 season. A potential posting was months away, major league scouts filled the stands for all of his starts, and yet rather than chase results, he chased development, going away from his wipeout splitter because he knew he needed to hone other pitches to offset his fastball.

To many, it was telling.

“He seems very solution-based, analytical in a forward-momentum way.” a front office executive said. “A lot of guys are deep thinkers and tinkerers and don’t give a s— about progress. They just give a s— about what fixes me right now. Sometimes, in order to fix yourself for the long haul, you need to take a step back and do an internal audit of what went right, what didn’t, and how to close that gap. He seems to have a high degree of accountability of what standards he has for himself.”